Performance

‘Jazz’ marching bands—who play kazoos—are native to the English North, Midlands and South Wales. Their long history entangled with the comic bands of the early nineteenth century, the brass and silver bands of former mining communities and US marching bands, performers draw on a wide range of popular music forms—but almost never jazz!

Tish Murtha—to date one of the few public figures to take an interest in jazz marching bands in the 1970s (when they were more often known as ‘juvenile jazz bands’)—didn’t have a high opinion of the groups that she photographed. Objecting to their ‘militarism’ and the politics of some of the organisers, she preferred the improvised ‘toy bands’, comprised of children not part of any established troupe, who play-acted at marching in the streets around Newcastle where Murtha worked.

But jazz bands remain a proud feature of the working-class communities who originated them, resilient in the face of industrial decline, fiercely independent and absolutely electric to watch. Performances are intergenerational, mixed gender and inclusive of disability, sexuality and race (although it remains a predominantly white, working class, notably hereditary practice).

Video by Lucy Wright. Cardiff, August 2025

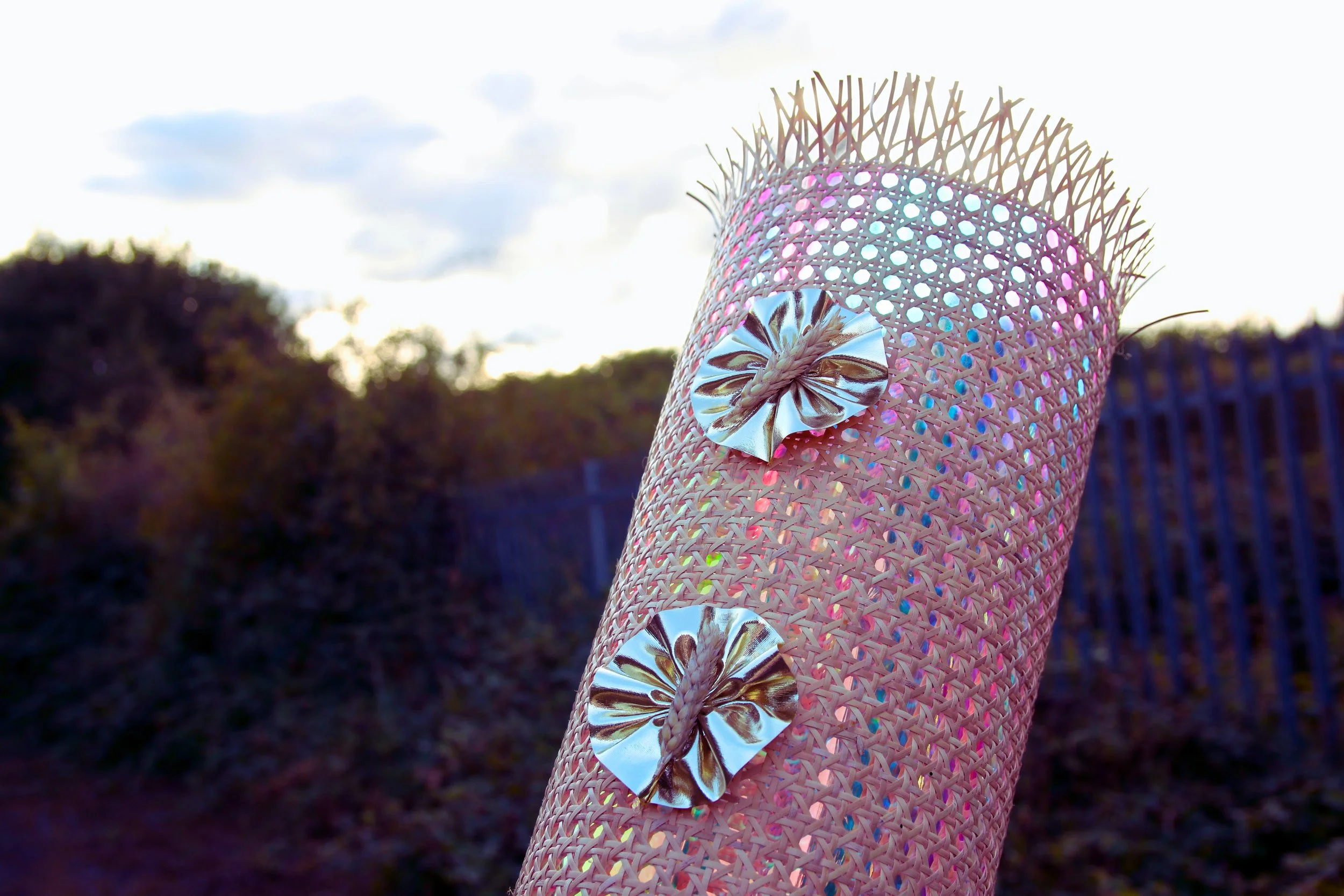

“I’ve been attending jazz marching band competitions since 2012, documenting this unique and little-known aspect of urban folk culture, which—like its close kin, girls’ morris dancing—plays a huge role in shaping the aesthetic sensibilities of the work I do as an artist.

Unable by way of geography and the significant time commitment to join a marching band myself—although I live in a miner’s terrace in a former pit village in Yorkshire—I created an informal performance as a ‘toy band’ of one, haunting the lanes and underpasses of a community which lost its carnival, wearing an improvised costume foraged from local charity shops and speaking to the beleaguered but not yet extinguished might of industrial folk culture.”