I wanna talk about folk and taste and how so often our determination of a tradition’s validity hinges on how well it meets our expectations of what folklore should *look* like.

It’s a dialectics that’s at the centre of my practice; imagining what our informal cultural heritage might be like if not for the assumptions created about it in that unusually fertile period of categorisation in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

(Older friends will know that I always insist on the distinction between the body of stuff compiled during that first folklore collecting boom, and the bigger picture of folk as a process, which could never be limited to a discrete time period or location).

But it’s also interesting to note that much of what we view as ‘good taste’ in the traditional arts—things that read to us today as rusticity, rootsiness, gestures towards the esoteric—were often the same things that rendered them ‘bad taste’ to the elites of their own era.

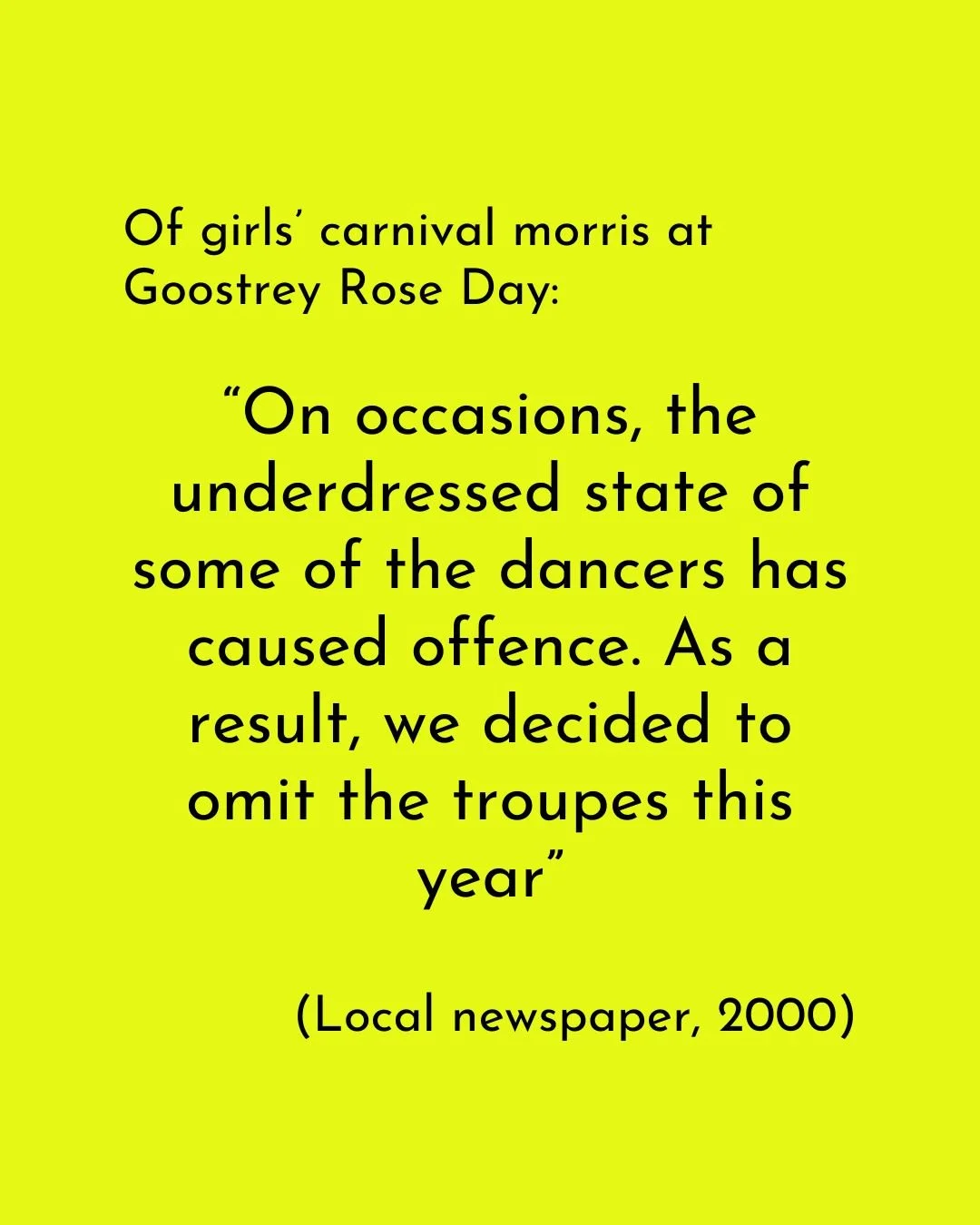

(I’ve pulled out a few quotes from my reading which demonstrate how practices determined as’ quaint’ today were sometimes considered wholly improper in their time—even on the receiving end of official sanction).

The other day I got into a bit of a flame war with someone on Facebook who objected to my sharing of the jazz kazoo band championships in a forum dedicated to traditional customs and folklore.

And I get it that this isn’t the sort of stuff they usually post there.

But their complaint was that the jazz bands aren’t authentically traditional, that they’re an American import (not true) and lack historical depth (also not true), not to mention that they’re less skilled than ‘real’ tradition bearers (SO not true).

Reading between the lines—fiercely upheld in the face of all contrary evidence—I concluded that they just *didn’t like* the performance. Perhaps it was too modern, too colourful, not sufficiently archaic. Or perhaps it evoked other things they found uncomfortable—like women, working-class people or military references.

And here’s the thing. I don’t always *like* EVERYTHING that I see in the traditional arts—although I flipping LOVE the jazz bands! I’m certainly no advocate for nationalism or glorification of the armed forces—and I’m not sure that most of the participants are either. But I also accept that folk is not a value judgement. Something doesn’t become less folk because I don’t approve of its politics or connotations.

There’s a complicated conversation to be had about dealing with instances when ‘the folk’ engage in something actively malignant—I’m thinking here of the flag-painted roundabouts we’re seeing everywhere just now—but denying this has any connection to folklore isn’t the answer.

One thing I know is that I will always admire the truthfulness of practices that remain firmly in the hands of the people who created them, which have adapted to stay relevant to different generations of performers, often under very difficult circumstances, and which reflect the real lived conditions of the world we live in today—the good, the bad AND the ugly.

Tell me that you’re worried about the rise of populism (me too). Tell me that military displays kind of scare you (me too). Ask me what the links are, if there are any (not direct ones as far as I know). Don’t tell me that stuff isn’t traditional because you don’t like the look of it.

As I’ve said many times before, folk is not another name for your snobbery.

—September 2025